Saturday, 31 October 2015

Friday, 30 October 2015

Key focus and directions

To start collecting Nihonto, one needs to set the Key focus and directions. Jean, a senior collector has taught me that there is a need for a theme in collecting so that it could be the goal for the collection. My key directions are:

1. To focus on collecting Koto katana before year 1460, preferably 鎌倉末期到室町初期 or earlier.

2. With Tokubetsu Hozon paper

3. Unique katana/Tachi

4. Focus on quality and not quantities, best that I can afford.

Originally, I was looking at Shinto (新刀) but with the good advice from Jean, I have changed my direction to Koto as koto were made as a weapon of war while the Shinto were made as decorations and ceremonial purpose. From my reading, it seems that the real art of Japanese sword making was lost after the warring period as the Shinshinto has made attempts to resurrect it. In another old articles, it was said that the wound cut by old katana will take a longer time to heal versus those of the Shinto.. Amazing...

Excerpts from the net:

There are several reasons why the old sword is the more valuable.

The wound inflicted by it is difficult to cure, though it be but a scratch one inch deep; while that made by a new sword heals easily even if it be deep. We know that the narrow, thin blade of the old sword is far sharper than the strongly made blade of the new. This is generally true, although there may be a few exceptions. At this time there are many fraudulent old swords made by polishing away the blade of the new sword. This is readily done, as the appearance of the welded edge of the modern blade is easily changed, and thus the ' midare ' may appear a ' straight' and a ' straight' may become like 'a midare.'

Old swords never change their character, Ichimoji always remaining Ichimoji however much it is whetted.

In the book "Notes on the New Sword," it is said, that "we must be well acquainted with the art of sword-cutlery or we become as the archer who is ignorant of the nature of the bow, or the doctor who does not understand medicine." The author further gives the details of cutlery concerning the new sword with which there is no difficulty. In the matter of polishing, we must admire it even if it be made to-day. We admire the old sword the more as its 'heat color' is lost with age and as its stuff iron presents peculiar marks, showing the lapse of 500 or 800 years. We can understand its meaning only by the study of the method of polishing. Of course the knowledge of cutlery is not positively useless. But even the Honnami of every generation do not study cutlery, while they are all perfectly acquainted with the modes of polishing. There are some men who commit the examination of their sword to a smith. But the arts of cutlery and judgment being quite different, the latter cannot be acquired without its special study.

The method of sword judgment relates almost exclusively to the old sword, but we can easily judge new blades without the knowledge of its rides. Many of the new swords bear the inscription of the maker. The structure of the nakago is very simple, being exactly similar to their pictures in the sword book. There are many very skillfully forged blades which have often obtained a better price than genuine work, for the reason that their value is fluctuating. This will be the case more frequently in the future.

Some new swords resemble the old work, and are much boasted of, but it is rather contrary to the purpose of the new sword, that being valuable only because it is new. The works of Sukehira and Sanemasa are noble, fresh, and lively.

We appreciate old swords that look new, but the new swords that look old from the beginning become useless after the lapse of a few hundred years. Even the old blade of which the welded edge is not clearly seen is useless. However slender its edge, good work will appear lively and newer than it really is. Some maintain that the new sword will benefit posterity, serving it as the "old," while the old sword will not be useful to future generations, having fulfilled its purpose. This seems reasonable. Still, always to select the new sword from such a motive is to sacrifice one's own welfare for posterity. This is very foolish, and may jeopardize one's life.

Mino Den Naoe Shizu 美濃伝

The MINO den and the Naoe Shizu

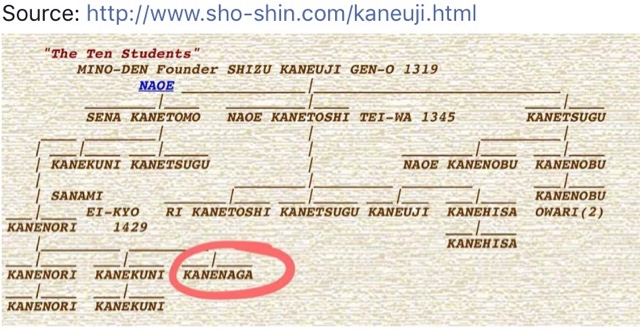

Source: http://www.sho-shin.com/kaneuji.html

This is a Tachi by Naoe Shizu Kanenaga from the Mino den with the HBTHK Tokubetsu Hozon paper. Kaneuji, one of the Masamune Juttetsu, established his forge at Shizu in Mino province. As such, Shizu has become to be used interchangeably with the Kaneuji for identification. Later his students Kanetomo, Kanetsugu, Kanetomo, and Kanenobu etc established their foge at Naoe in Mino and became known as Naoe Shizu.

This Tachi is from the late Nanbokucho era to early Muromachi era. This is a unique Tachi as rarely do the HBTHK put down the period at which the Tachi were made, but this one has the period written on the certificate. In addition, many of the Naoe Shizu school's katana were mumei, unsigned. Collecting signed Tachi will help new collector like me as it gave the much informations needed. In addition with the certification, it will also made my brining the katana back to Singapore easier as I could proof to the Police that it's a real antique from the early Muromachi era. I am very happy and proud to be able to find this Tachi..

Cutting edge : 70.5cm

Sori: 1.8cm

Jigane: Strong Itami-Hada and Masame-hada

Hamon: Suguha and Ko-gunome with Ko-Nie

Boshi: Sugu-Komaru nijyuha gokoro

Signature: Kanenaga

Koshirae: Shirasaya

This rare tachi by Naoe Shizu Kanenaga and has a length of 70.5cm and a lovely curvature. It dates back 650 years to a significant time in Japanese history called the Nambokrcho period – also known as the Northern and Southern Courts period. During this era, there existed a Northern Imperial Court in Kyoto, and a Southern Imperial Court in Nara. Ideologically, the two courts fought bitterly for fifty years, with the South giving up to the North in 1392. As the old Tachi was made as a weapon, to be able to be kept in good condition is not an easy task.

Additional information from the various sites :

To gather a Gokaden is every collectors' dream...

Naoe Shizu Kanenaga 兼長Taichi 美濃伝 南北朝末期~応永

Naoe Shizu Kanenaga 兼長Taichi 美濃伝 南北朝末期~応永

This is mt first serious Nihonto. After my first unpleasant experience, I have learnt to be careful with purchase. It is a Naoe Shizu Kanenaga's sword, a very rare item in the world according to the Japanese dealer. Naoe Shizu school is very famous school. However many books make an article, but there are not many sword of Naoe Shizu school.

This Kanenaga have a NBTHK Tokubetsu Hzon certificate paper. This kanenaga is not normaly Mino school and It's special order sword.

Cutting edge : 70.5cm

Sori: 1.8cm

Jigane: Strong Itami-Hada and Masame-hada

Hamon: Suguha and Ko-gunome with Ko-Nie

Boshi: Sugu-Komaru nijyuha gokoro

Signature: Kanenaga

Koshirae: Shirasaya

This rare Tachi by Naoe Shizu Kanenaga and has a length of 70.5cm and a lovely curvature. It dates back 650 years to a significant time in Japanese history called the Nambokrcho period – also known as the Northern and Southern Courts period. During this era, there existed a Northern Imperial Court in Kyoto, and a Southern Imperial Court in Nara. Ideologically, the two courts fought bitterly for fifty years, with the South giving up to the North in 1392.

Japanese sword evolution

Japanese katana production can be divided into specific time periods:

1. Jōkotō (ancient swords, until around 900 A.D.)

2. Kotō (old swords from around 900–1596)

3. Shintō (new swords 1596–1780)

4. Shinshintō (newer swords 1781–1876)

5. Gendaitō (modern swords 1876–1945)

6. Shinsakutō (newly made swords 1953–present)

Fujishima Tomoshige katana (友重)

友重 Smith is Fujishima Tomoshige. Fujishima is the name of a place in Echizen Province and it is said that the first generation of Tomoshige lived here first then moved to Kaga Province

The founder of the Fujishima school was Tomoshige, a pupil of Rai Kunitoshi. His work dates to 1334-1338. Smith is Fujishima Tomoshige-mono or majiwari-mono. The characteristics of the swords of the Fujishima school tend to combine the traits of two or three of the Gokaden (five main schools). Some said that it brings Yamato and Soshu styles to mix.

Certain of the Fujishima smiths, and the later Sanekage school smiths, worked in one or more of the basic traditions and incorporated several of the characteristics of these schools into their work.

Tomoshige and Nobunaga tempered gunome-midare with sunagashi in nie-deki which reminds one of Sue-Bizen smiths and Nobukuni of Yamashiro Province. I have seen sugu-ha of Tomoshige and gentle notare of Nobunaga with hotsure and sunagashi. They normally forged ko-itame-hada or ko-itame-hada combined with masame. I have seen pure masame-hada by Nobunaga. Tomoshige occasionally makes wakizashi and tanto in kanmuri-otoshi-zukuri that was favoured by Yamato smiths. There are some extant works with the mei of ‘Fujishima Yukimitsu’. Yukimitsu tempered notare-midare and Kiyomitsu favour tempering chu-sugu-ha and hiro-sugu-ha, rather than gunome-midare. The production age of the extant works by Kiyomitsu is limited to the Genki and Tensho Eras.

Gokaden

For any one who is keen to start collecting, one needs to know the Gokaden, which is the five basic style of Japanese sword. However, in reality, one can often see mixed signs as well.

Gokaden***Five basic style of Japanese Sword***

|

From ancient times, five areas where produced numbers of great swordsmiths were equally blessed with several good conditions, such as in political aspect, in business and rich in raw materials for making sword. No wonder many smiths flew in these core part continuously from all over the country and brought about a great advance in research and development. Each producing district established their own style and initiated their technique into posterity and also influenced local smiths a great deal. These are the five main districts where they showed distinctive competency above all. "Soushu-den", "Bizen-den", "Mino-den", "Yamashiro-den", and "Yamato-den". These were named generically "Gokaden" in Edo period and judge of swords are basically relied on each of these style.

|

相州伝

| Soushu-den started in late Kamakura period under the effect of Kamakura Shogunate and completed by smith in Nambokucho period as Akihiro and Hiromitsu and so on. Generally nie, chikei, kinsuji, inazuma are typically seen inside the blade. |

| Prominent swordsmiths : Hiromitsu / Akihiro / Hasebe Kuninobu / Masakage / Tametsugu / Samonji / Rai Kunimitsu / Taima / Naoe Shizu / Kanemitsu / Nagayoshi / Hiromasa / Masahiro / Yoshihiro / Shimada / Nobukuni / late Hasebe | |

備前伝

| The most numerous swordsmiths existed in Bizen. Number of schools flourished for centuries that it is hard to explain collecively. So it can classify into several ways as ko-Bizen, ko-Osafune, Ouei Bizen, Sue Bizen. "Koshi-zori" is conspicuous as it gets older. "Jigane" is pliable and "utsuri" appears like shadow between "shinogi" and "hazakai". These are remarkable features of Bizen. "Hamon" is mainly "chouji-midare" but it has transformed to "gunome-midare" as time go by, also "nie-deki" changes to "konie" then "nioi-deki". |

| Prominent swordsmith : <Ko-Bizen>Tomonari / Masatsune / Sukehira / Kanehira / Yoshikane / Norimune / Sukemune / ko-Ichimonji / ko-Aoe <ko-Osafune>Mitsutada / Nagamitsu / kagemitsu / Mori'ie / Sanemori / Masanaga / Chikakage / Katayama Ichimonji / chu-Aoe <others>Kanemitsu / Motoshige / Nagayoshi / Morikage / Morimitsu / Yasumitsu / Norimitsu / Moromitsu / Tsuneie / Iesuke / Sukesada / Kiyomitsu / Katsumitsu / Norimitsu | |

美濃伝

| The forging pattern on hiraji is mainly itame and mixed with "masame" and "mokume", "shinogi" is "masame". This forging style is a technique to make blade solid and extremly sharp. Inside the blade, unique "hataraki" called "seki-utsuri" is appeared faintly white with "jinie". Tempering pattern is formed by "nioi" basic "nie" entangled. After the battle of Sekigahara in 1600, so many swordsmiths spread all over the country from Mino ,because of its functionality, that Mino-den became standard way of making swords in Edo period. |

| Prominent swordsmiths : Kaneuji / Naoe Shizu / Jumyou / Yoshisada / Akasaka Senjuin / Kanemoto / Kaneusa / Ujifusa / Kanetsune / Kanesada / Daidou / Muramasa / Sanjou Yoshinori / Fujishima / Unshu Yoshii / Naotsuna / Takada / Doutanuki / Heianjou Nagayoshi | |

山城伝

| The tradition of Yamashiro swordsmiths have started from Sanjou Munechika in late Heian period. Typical figure of those times is narrow bladed Tachi which line is beautifully curved with small kissaki. Well forged "jigane" is mostly "koitame" and "komokume" but some are "nashijihada", and the uniformed "nie" appears finely. Fundamental "hamon" are "suguha" and "komidare", tanto of "suguha" is the most strong point of Yamashiro's. |

| Prominent swordsmiths : Sanjou Munechika, yoshi'ie / Gojou Kanenaga, Kuninaga / Awataguchi / Ayanokouji Sadatoshi / Rai Kuniyuki, Kunitoshi, Kunimitsu, Kunitsugu / Ryoukai / Nobukuni / Heianjou Nagayoshi / Shintougo Kunimitsu / Yukimitsu / Chiyozuru Kuniyasu / Inshu Kagenaga / Bungo Sadahide / Yukihira / Bungo Ryoukai / Enju | |

大和伝

| Yamato-den derived from five big schools. They are Senjuin, Tegai, Taima, Houshou and Shikkake. The source of their names are all from temples that swordsmiths belonged exclusively to each temple. Common style of these schools are Tachi with high "shinogi" and wide "shinogiji". Tempering pattern are "masame" and "itame" incline to "masa". Hamon is "suguha" with strong "nie", mixed with several "hataraki" as "hotsure" which looks like loose thread and many "sunagashi" inside hachu. "Yakihaba" becomes broad as it gets to "kissaki" and "yakizume" at the top. |

Source:

http://world.choshuya.co.jp/gokaden/

Japanese Imperial Naval officers dirk

This is an example of the Japanese Imperial Naval Officer’s Dagger, as authorized in 1883 (Meiji 16). Although adopted some 59 years before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, these daggers remained in use through the end of World War II. The Japanese military in the modern era required their officer’s to purchase their own uniforms, equipment and personal weapons, just as nearly every major military force in the world did. As such, even though standardized regulations were in place for every conceivable item an officer might need, variations did exist – especially within the realm of edged weapons like swords and dirks. This is a Japanese Russo war, WWl Naval tanto dagger in kaigun tanken mountings

Many of these naval tanto were made by machines but there were exceptions where some officers used their traditional tanto blade and custom made into the design of the naval Dirk. As you can see, I have taken one small step from the mini sword to a small Tanto.

The old blade is signed "Shigeyoshi 重良", hira-zukuri shape made during the 室町時代Muromachi period ca.1550 era. The blade is in old polish and the temper line is chusuguba with konie active temper throughout the blade and deep temper. Brass fittings are cherry flower motif engraved brass fittings with locking mechanism. It measures 9+1/2" cutting edge and 15+1/2" in mountings. As such, this is a Samurai Tanto remodeled into naval Dirk. Not many of these naval Dirk survived as many were at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean. As a former history student, these historical items are important for us to remind human race not to make the same mistakes.

Mini Tanto 19th century

According to the seller who sold this to me, this is a Mini Tanto from the 19th century, 5.8 inch cutting edge in fine polish with the signature above the ridge line, very nice blade in beautifuly crafted aikuchi koshirae. For many Nihonto collectors, this mini knife is not considered the real Nihonto. For me, this is important as its a beautiful knife with Maki E. In addition, it is this mini Nihonto that got me started to explore into the world of Japanese swords.

koshirae has a samurai poem on it, under the poem is the name of the man who wrote the poem, called Koutoku. The blade has the signature of Kiku Ichimonji, living and working at the end of 19th century.

there is a nice link(http://www.kikuichimonji.co.jp/h.html) here about him, at the end of samurai era and carrying swords and he made commercial items, cooking knives and tools, but as you can see he made nice tanto also, so this is a rare example with a nice history and well documented.

The japanese man who translated it found it difficult as old type of writing style and poem, but it is something like : life is like a cherry tree, it blooms beautifuly and falls when it end. Also see http://www.kikuichimonji.com/

KIKUICHIMONJI

In the year 1208 the Emperor Gotoba gave permission to his swordsmith Norimune to stamp the blade of each sword with the imperial Chrysanthemum-crest. Norimune then engraved the number 1 below the crest. Thus the name Kikuichi-monji, Chrysanthemum One, was created.

In 1876, when samurai were banned from carrying swords, Kikuichi-monji added a horse’s bit mouthpiece(kutuwa) ” “ logo above its name and started manufacturing cooking knives, carpentry tools, gardening knives, and other related products in Kyoto. Using the superb sword-making technique passed down through generations, Kikuichi-monji pledges to produce high-quality cutlery.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)